Throughout his presidency, Mr Barack Obama has been steadfast in his reluctance to send American forces back to war. He stubbornly, and quite courageously, resisted pressure to take a bigger role in Libya or to intervene in Syria, and, just a few months ago at West Point, he explained why, eloquently defending his view that American armed force was seldom the answer to the world's problems.

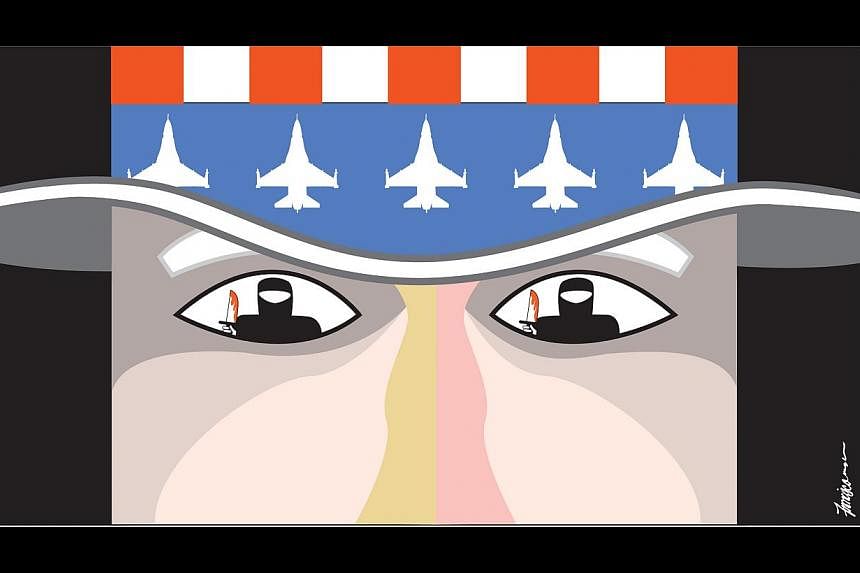

Now he has changed his mind and gone back to war in the Middle East, because events over the past few months have forced him to confront three realities about the situation there.

The first reality is that, despite efforts by the United States over nearly a decade of occupation, Iraq faces a crisis almost as profound as Syria's. Mr Obama had hoped that, once he had withdrawn US forces, Iraq would find its feet as a state and society.

Now it, too, faces a full-scale civil war, which is so deeply connected to Syria's that they have become in effect one conflict.

The second reality is that neither Iraq nor Syria is likely to survive these conflicts in the form they have existed since the Ottoman Empire collapsed. Once the fighting subsides - and that may not be for many years - the political map of the Middle East will most probably have been transformed. New national borders will replace the colonial boundaries imposed by Britain and France after World War I.

And this process might well spread beyond Iraq and Syria to engulf Lebanon and Jordan, and perhaps even Saudi Arabia. The era of secular authoritarian republics and conservative fundamentalist monarchies will pass, and no one knows what will replace it.

The third harsh reality is that the new Middle East that eventually emerges from this mess is likely to be even more volatile, even more hostile to the West, and even more threatening to Western interests in the region, than the last one.

These realities have suddenly become clear in Washington and elsewhere around the world because of the spectacular emergence of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) into the spotlight over the past few months.

But ISIS itself is only one part of the picture, and not by any means the most important part.

The group's seemingly-spectacular military successes and flair for publicity have exaggerated its significance in current events and in the region's longer-term future.

Whether it will survive as part of the Middle East's new political map is uncertain. But its brutal actions and recent successes offer a chilling glimpse of how the region's future might evolve.

First, it shows how the new political map of the Middle East is likely to be drawn along religious lines, creating a patchwork of smaller states, each susceptible to radical fundamentalist ideologies and bitterly hostile to its neighbours. Second, it raises the fear that such regimes will be brutally repressive of the people under their control. And third, it confirms that they are likely to be relentlessly hostile to the West.

Nonetheless, ISIS remains just a symptom of these problems, not their cause. And that suggests that while President Obama is right to be worried about trends in the Middle East, he is wrong to believe that the US can respond effectively to them by focusing so narrowly on degrading and destroying ISIS itself.

Some Western leaders are focused on ISIS primarily because of the risk that it will sponsor terrorist attacks against their countries. But it is not clear that ISIS itself really does pose a new or qualitatively graver risk of anti-Western terrorism.

In particular, the danger that Western extremist fighters returning from the Middle East will launch attacks at home is real, but it is not new. This danger can never be realistically eliminated, but it can be managed with effective police and intelligence work, as it has been ever since the Sept 11, 2001 attacks. Bombing ISIS won't do much to help that effort.

In any case, concerns about terrorism are probably not what has finally goaded Mr Obama into sending US forces back to the Middle East. Rather, it is the sense that the region's whole strategic and political order is slipping out of the US' control. For decades, the US has struggled against great odds to preserve and reinforce its place as the leading influence over Middle Eastern affairs.

It has been a long and often sad story, from the fall of its ally the Shah of Iran 35 years ago, through the Iraq-Iran War, Iraq's invasion of Kuwait, and the disaster of the US-led invasion and long occupation of Iraq.

The collapse of Iraq and Syria, and the emergence of groups like ISIS, seem to show that this struggle has now been lost. And Mr Obama's tragedy is that the military measures he now contemplates will not rescue the situation, but simply reinforce the US' growing irrelevance to what happens on the ground there.

The harshest reality of all is that the US and its Western allies can do little to shape the new map of the Middle East, politically or militarily.

There is lots of talk in Washington about exercising leadership to encourage and facilitate the emergence of a new, stable and inclusive government in Baghdad. But it is simply an illusion that the US has the capacity to shape Iraqi politics that way.

Likewise with the military effort. It is clear that the US cannot defeat ISIS, or influence the wider pattern of events in Iraq and Syria, from the air. Only ground forces can make a real difference. But the debate in the US about whether it should commit its ground forces to the fight is quite unrealistic. Even if it decides to commit all its available army and marine units to the campaign, as it did during the occupation of Iraq, Washington would be no more able to determine the region's political future than it could then.

The simple fact is that the only countries that can shape the region's future are the region's countries themselves, especially its major powers: Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Egypt. Whether, and if so how, they can work, separately or together, to protect their shared interests in the future of their own immediate neighbourhood will make much more difference than anything the US can do to shape the Middle East. Making this clear might prove to be the most important result of Mr Obama's new Middle East war.

The writer is professor of strategic studies at the Australian National University, Canberra.